Wood: everything you need to know

Hi there! How do you do! I don’t know about you, but the more I get into the world of whittling and wood, the more I realise the desperate need I have to know things in more depth. Not only to satiate a hunger for culture, but more so because you gradually discover that you have thrown yourself into a great adventure, without having the basics.

I could swear that, in the various groups on Facebook, (⏰ehi! By the way, have you joined the showcase woodcarving group?) at least 80% of the users have started to try their hand supported by books, or following video tutorials, to be guided to a more or less immediate result. Nothing wrong with that, this is also my path, no matter what road you take, the really important thing, for me, is to try and start.

If, however, now that we have started, we take a step back, we can find out how to do the job more competently and confidently and take home a much better result. If, on the other hand, the problem wasn’t one of knowledge but of manual dexterity, well, we’ll settle for general knowledge and a pat on the back for having tried anyway! 😂😉

I realised that we can’t talk about types of cuts, techniques and so on without first seriously facing our material. Wood. So let’s start right from the abc.

The wood structure

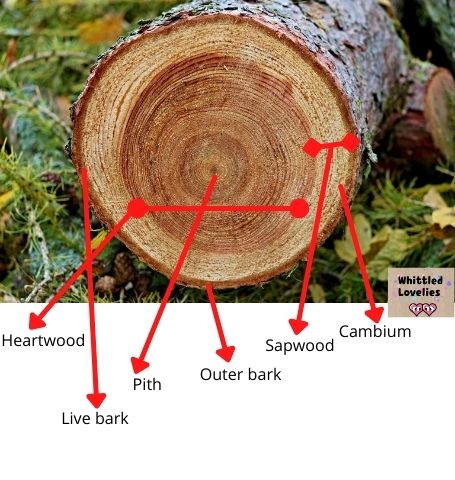

Every woody plant in a temperate climate grows radially in spring. This means that every year a new ring is added around the pith, which is the innermost, central part of the wood, a layer of new wood between the old and the live bark, the membrane closest to the outer bark. The thin tissue that forms this layer is called the cambium.

Although it is only the cambium that produces the tree’s growth, all the various tissues also have active functions with vital cells, conducting vessels, fibres and are responsible for carrying water and mineral salts vertically from the roots to the leaves, which are necessary for the tree’s proper nutrition.

The conducting vessels are called grains, they are the typical marks of wood, the part that ultimately interests the woodworker most, from the carpenter to the carver. They are different and characteristic for each type of tree.

Each part of the trunk performs a specific function: the live bark contains the vessels that carry the nutrients synthesised by photosynthesis from the leaves to every part of the tree. The inner bark, called sapwood, formed by living cells, is responsible for the conduction of mineral salts from the roots to the leaves. The outer bark, although made up of dead cells, allows gas exchange.

After a few years the tree starts to age and the inner parts begin to die. The conduits that were active in the movement of nutrients until a few years before are filled with gum, resin or air, depending on the type of plant. When this process is activated, the dead part is called heartwood.

Heartwood and sapwood

Heartwood is normally the darker part of the tree than the sapwood, which remains the active part of the tree, but these colour variations are more noticeable in some types of tree and invisible in others. This heartwood is the most commercially valuable part of the tree, and is commonly referred to as solid wood. Being safely inside the tree, it is also the least susceptible to pests.

The percentage of heartwood refers to the age of the tree, the amount of sapwood can be more or less large or consistent depending on whether the tree is in good soil or not, isolated or constrained by other plants that prevent its regular growth.

Fine-grained wood and coarse-grained wood

Other words that always come up when we hear experts speak are: fine grain or coarse grain. But what exactly are they?

This is the porosity of the wood and its density. The more compact the wood, the more likely it is to have very small or tiny pores. The term porosity refers to the amount, positioning and size of the vessels.

Greater porosity is usually typical of light woods as they are less dense, less compact and therefore have more air in them. One thing that should not be confused is lightness in terms of specific weight with tenderness, and its opposite, heavy wood with hard wood. They are two completely different things! (This confusion is more typical in Italian, as two misunderstandable terms are used)

All these factors must be taken into consideration at the time of cutting, choosing the most appropriate means. As we have seen in the case of balsa, for example, it is better to work with a knife rather than a saw. Moreover, this knowledge has a major impact on the final results, such as polishing. Knowing how to recognise the porosity of the wood also makes it possible to decide whether to apply finishing varnish to close the pores or how to proceed in case of pests.

Hard and soft wood

How many times have we come across this choice! The question we often ask ourselves, is it better to have a soft wood or a hard wood, causes us confusion every time, but the answer is quite banal, it all depends on the use we want to make of the wood!

If we want a durable wood to build a piece of furniture, which will certainly be assembled and processed with mechanical machinery, it is certainly better to deal with a hard wood. Generally speaking, it will provide excellent resistance to wear, impact and a certain solidity.

If, on the other hand, we are thinking of carving a small ornament, which requires the use of a knife or manual tools, it is better to use soft wood. We will make less effort and for the use of the object itself it is not so important that it is solid or that it gives problems with wear.

The hardness of wood is related to its density. When the fibres are dense, compact and tight, the wood is practically inelastic, therefore not very porous and resistant to damage, but it should be remembered that this makes it more fragile to breakage than flexible wood.

But how do you recognise which tree has hard or soft wood?

The simplest answer is obviously to learn by memory and remember. There is also a rather general and empirical method, which can be applied and even if it is not 100% valid it can help: if the tree is a broadleaf tree, i.e. it loses its leaves in autumn, it is a hardwood, if the tree is an evergreen conifer it is a softwood.

Since hardness is also related to the amount of water the plant needs to live, therefore to its porosity and its ability to retain liquids, as a general rule, we can assume that an arid soil is more likely to host hardwood trees than a moist soil that naturally hosts softwood trees.

| Softwood | Hardwood |

|---|---|

| Fir (Abies) |

Maple (Acer) |

| Cedar (Chamaecyparis) |

Alder (Alnus) |

| Cypress (Cupressus) |

Birch (Betula) |

| Larch (Larix) |

Hickory (Carya) |

| Spruce (Picea) |

Hornbeam (Carpinus) |

| Pine (Pinus) |

Chestnut (Castanea) |

| Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) |

Beech (Fagus) |

| Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) |

Ash (Fraxinus) |

| Thuja (Thuja) |

Walnut (Juglans) |

| Hemlock (Tsuga) |

Sycamore (Platanus) |

| Aspen, poplar (Populus) |

|

| Cherry (Prunus) |

|

| Willow (Salix) |

|

| Oak (Quercus) |

|

| Lime, basswood (Tilia) |

|

| Elm (Ulmus) |

|

| Kauri pine (Agathis australis) |

|

| Iroko (Chlorophora excelsa) |

|

| Rimu, red pine (Dacrydium cupressinum) |

|

| Palisander (Dalbergia) |

|

| Brazilian rosewood (Dalbergia nigra) |

|

| Ebony (Diospyros) |

|

| African mahogany (Khaya) |

|

| Mansonia, bete (Mansonia) |

|

| Balsa (Ochroma) |

|

| Nyatoh (Palaquium hexandrum) |

|

| Afrormosia (Pericopsis elata) |

|

| Meranti (Shoreaa) |

|

| Teak (Tectona grandis) |

|

| Limba, afara (Terminalia superba) |

|

| Obeche (Triplochiton scleroxylon) |

Source Iarc Lyon France

Now, after reading this table, I bet many of you will be puzzled. How is it possible, after they have explained to us that the perfect wood for knife carving is lime, birch, maple and we see with our own eyes that the knife sinks like butter that these are found in hardwoods!

Physical characteristics

In fact, the first misleading thing is the common definition we have of these woods. It would be better to define soft wood as sweet, hard wood as strong. We have not been taught wrong, the woods mentioned above are in fact perfect for carving, but in the light of considerations about the physical properties of the various woods.

We often forget that it is precisely these characteristics that need to be assessed when designing, rather than the softness or hardness of the wood. Returning to the example of the particular balsa wood, knowing that it is a hard wood we would not want to try to carve it by hand, but instead it is softer than butter. Because its physical characteristics of porosity and density make it so, its strength is shown in its resistance and its fragility in uses other than carving.

Therefore, each wood should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to see whether or not it meets the requirements of suitability for our projects. Imagine if we wanted to make a floor in a shop that had to withstand the daily wear and tear of millions of footsteps and we did it with a wood that was not very resistant to this use, we would soon have thrown away our work and our money.

The properties of wood

There are four main properties to consider when choosing the right wood for your project:

Wood cuts in carpentry

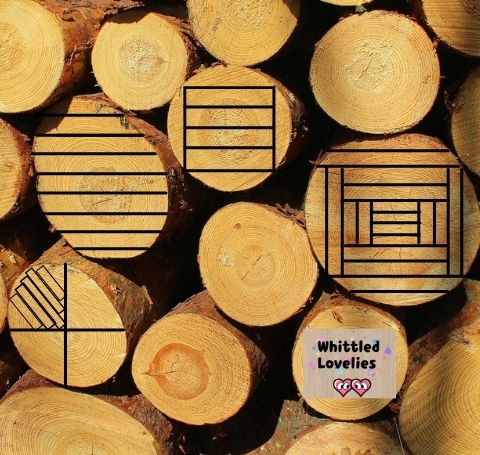

There are different types of cuts that the carpenter may choose to make when he wants to split a log of wood. As this is a job that will produce boards for sale, the primary aim is obviously to maximise profit and minimise waste.

This is not always possible as we also try to evaluate the aesthetics of the piece, so sometimes it is worth making a cut that involves more waste just to emphasise the beauty of the texture and grain.

The types of cuts you see in the picture are among the most commonly used. It is about cuts:

- cantibay

- plainsawn

- parallel

- quartersawn

Each cut has its pros and cons, whether in terms of waste, beauty or difficulty of execution. They are chosen by professionals on the basis of how the end user will use the timber.

Quartersawn (bottom left), for example, while not the most practical and producing the most waste compared to other types, is highly valued. Some woods such as oak, to name but one, are much more commercially valuable when quartersawn as the effect of the grain is brought out to the full.

As you will have noticed, the topic is very broad and very interesting, but I hope I have given you a hand in clarifying some of your doubts. In any case, always remember that comments, questions, corrections, insights are very much appreciated, I look forward to the next article! Bye! 😘😘

This is an article written by a human for humans!

All articles in the blog are written by me. No contributors, no people paid to write content for me.

Posts written by guests or friends of the blog are marked under the title with the words “guest post.” These are friendly collaborations, contributions to the carving community.

No AI (artificial intelligence) support is employed in the writing of blog articles, and all content is made with the intent to please humans, not search engines.

Do you like my content?

Maybe you can consider a donation in support of the blog!

Click on the button or on the link Ko-fi to access a secure payment method and confidently offer me coffee or whatever you want!

From time to time, in articles, you will find words underlined like this, or buttons with the symbol 🛒. These are links that help deepening, or affiliate links.

If you are interested in a product and buy it suggested by me, again at no extra cost to you, you can help me cover the costs of the blog. It would allow me to be able to give you this and much more in the future, always leaving the content totally free.